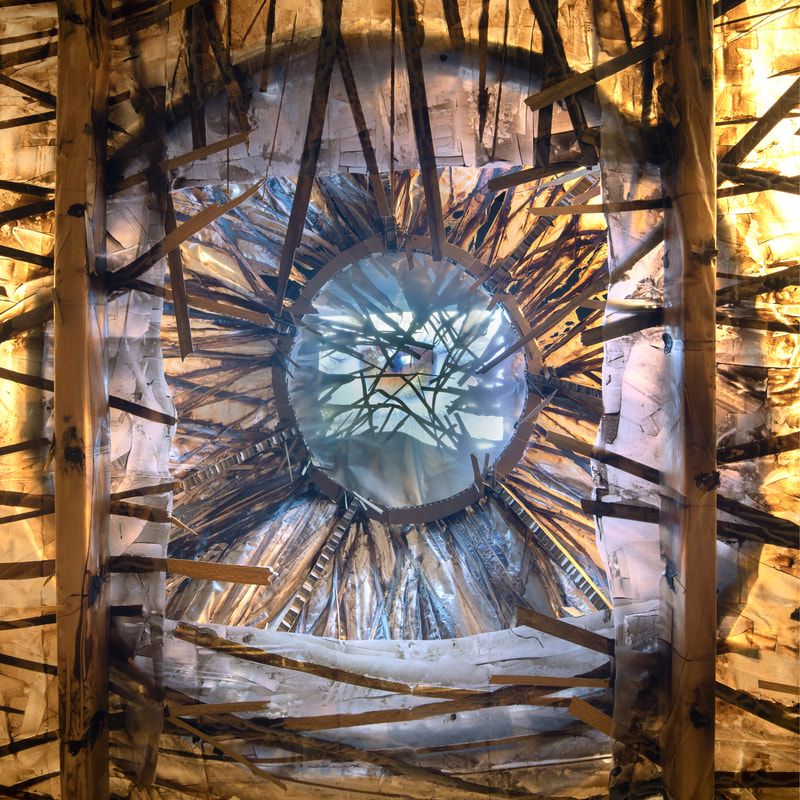

Adalaad London Gordon Gallery, Rishon-LeZion, 2017

Curator: Efi Gen

Photos by: Liat Elbling and Tal Nissim

Adallaad

May be she is the creator,

May be she is using the existing world

And perhaps she creates a variant for either compassion or horror: a state which materializes as a place of worship for one of the aspects of an alternative deity.

The Sheikh’s tomb[1], was selected by the artist as a local icon, embodies an identification of the middle-east, is replaced in Ritov’s installation to a semi-transparent space covered with artificial plastic “earth-sheet”[2] . Out of the installation’s dome emerges a video screening: marking Adallaad’s all-seeing eye[3]. At the background, sounds of drops\trickling water in a cave combined with drum rhythmus eco, reminds a tribal worship ritual. The combination between the semi-transparent earth covered walls with the screening from the dome above, create the sensation of an underground space, somewhat buried for self-inspection and for being exposed; as if the structure invites to step inside to contemplate, to listen and to feel examined. The viewer turns into an object, while observed, as he is being inspected by the clear eye of She who sees everything. All this while one can look back to witness Adallaad’s epiphany. He is now at the holy of holies of her shrine.

Adallaad is a major goddess and since antiquity she is in charge of memory/documentation/registration. Adallaad is the product of a desperate effort, maybe for the last time, of a system collapsed into itself. She is the guardian of the things, one moment before they transform from being ‘things’ to being ‘Culture’, open to contemplation and discussion. She is passive, unable to provide interpretations to events, she is functioning within a tragic tension since she sees everything, while presumably the things themselves contain all possible interpretations. Adallaad is the impossible representation of things which happen before we perceive them. Adallaad is available and existing, but any attempt to apply or take hold of her is doomed to failure – she disappears (similarly to Lacan's idea of “The real”). At the moment we pay attention (perceive or point) on a thing, we already apply our personal prejudices and initial concepts, thus we transform it to a narrative. The observer in Ritov’s installation is offered to try to delay his need to look after an agenda, and to remain in a state devoid of judgement. A paradoxical state. Adallaad embodies this tragic state, she points on our inability to grasp the things themselves and we are doomed to stay in a world of ghostly narratives.

Ritov use well known Israeli local symbols identified with the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. By shifting the symbols visuality out of their familiar context, she manipulates their apparent form to look initially as innocent and beautiful, which after further scrutiny are disturbing and menacing. She applied this method in her previous drawings of illegal settlements on masking-tape, and later on instruments of war presented as butterflies.

This line of thought expresses an attempt to cope with our historical space-time while proposing a possible solace in a new belief, in a new world order, a world where the infinity of the memory will bring a new meaning. The mere existence of Adallaad as the memory Goddess who sees everything, might give some more weight to the human action. Adallaad emerges from philosophy - to the place; from history - to the present, while she demand the observer to think in a critical way on the relation between narratives - places - worship and its projection on history, local and human.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Square structure with a dome, opaque, made of stone. A place of worship and prayer according to the qualities attributed to the person buried in it.

[2] Earth sheet: The given name of the medium technique (the material) which the installation is made of - adhesives, medium gel acrylic, pigment and veneer on plastic sheet. The material looks like muddy soil that covers the Sheikh’s tomb in a semi-transparent manner, so one can see through it alternately both inside and out.

[3] It may be appropriate to think about Adallaad as the feminine analogue of the ‘The angel of history’ which was introduced by Walter Benjamin in 1940, just before his death, as part of his well known ‘Ninth Thesis on the Philosophy of History”, written out of inspiration from Paul Klee‘s ‘The Angelus Novus’. He saw in this image the ‘The angel of History’ who remembers the past and worries about the future of the human race.

IX ...“A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress”...